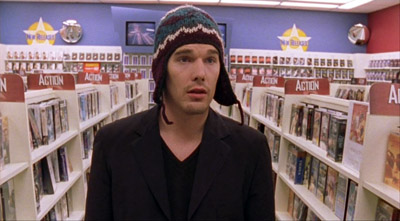

I discovered this weekend that the 1999 Ben Stiller movie Mystery Men was finally on Netflix. When my kids were younger I kept coming back around to it as something I wanted to show them, given the rise of superhero movies, but it was never available for streaming. This one’s weird, it’s more of a “super anti-hero” movie where a bunch of normal guys with arguably no powers at all wish they were heroes. You’ve got Paul Reubens as “the spleen”, who farts at people as a weapon, Hank Azaria as the fork flinging Blue Raja, William H Macy as the Shoveler (“God gave me a gift. I shovel well, I shovel very well”) … the list goes on, all easily recognizable character actors. Janeane Garofalo as “The Bowler”. Ben Stiller as “Mr. Furious”. You won’t necessarily like him when he’s angry, but you won’t have to worry too much about it.

Why are we talking about this? Because when we sat down to watch it I noticed something I hadn’t seen twenty years ago – William H Macy delivering his version of Henry V!