‘Still Dreaming,’ a documentary that in many ways is a sequel to another film I (Hank, not Duane) directed called ‘Shakespeare Behind Bars,’ will premiere on PBS starting this Saturday, April 14.

STILL DREAMING is a multi-award winning film about the powers of creativity, and how engaging in art-making can deeply enrich our lives at any age.

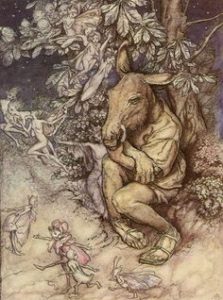

Filmed at The Lillian Booth Actors Home just outside New York City, where a group of long-retired Broadway entertainers dive into a production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and find that nothing is what it seems to be. With a play that is usually about young love and sex farce, this ensemble finds that for them, the themes of perception, reality and dreaming deeply resonate.

Filmed at The Lillian Booth Actors Home just outside New York City, where a group of long-retired Broadway entertainers dive into a production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and find that nothing is what it seems to be. With a play that is usually about young love and sex farce, this ensemble finds that for them, the themes of perception, reality and dreaming deeply resonate.

This wistful, honest, and frequently hilarious documentary follows the rehearsals as opening night approaches. Tempers flare, health concerns abound, and disaster seems imminent. But as these former entertainers forge ahead, they realize that creativity is a magical force of renewal.

This whole film journey started back in 2009, when I went to the Lillian Booth Actors Home to meet with the Shakespeare group there to discuss the possibility of their doing a play and my filming that process. The residents and staff were all very supportive of the idea right away, so the discussion quickly turned to which play they would do. The residents in particular were very enthusiastic about the possibility of re-connecting with their craft, for it was as one put it, “This is my whole life inside, and this is a way of getting all of that back.”

My co-director, Jilann Spitzmiller and I went in with the idea of Romeo & Juliet, but that was met with very little enthusiasm, and so a discussion ensued mostly around comedies, since as one resident jokingly put it, ‘There was enough tragedy in their day to day lives already.’ They did discuss Macbeth, King Lear of course, with its theme of old age, and one point someone suggested The Tempest, but I quickly rejected it since it was the play done in ‘Shakespeare Behind Bars.’ The residents kept coming back to comedies such as Taming of the Shrew, As You Like It, The Merchant of Venice, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It was Midsummer that seemed to gain the most backing since it was a comedy, and had an ensemble cast with no real leads. This was good they felt since it wouldn’t fall on one or two actors to carry the whole production, which seemed like too much pressure at their age.

My co-director, Jilann Spitzmiller and I went in with the idea of Romeo & Juliet, but that was met with very little enthusiasm, and so a discussion ensued mostly around comedies, since as one resident jokingly put it, ‘There was enough tragedy in their day to day lives already.’ They did discuss Macbeth, King Lear of course, with its theme of old age, and one point someone suggested The Tempest, but I quickly rejected it since it was the play done in ‘Shakespeare Behind Bars.’ The residents kept coming back to comedies such as Taming of the Shrew, As You Like It, The Merchant of Venice, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It was Midsummer that seemed to gain the most backing since it was a comedy, and had an ensemble cast with no real leads. This was good they felt since it wouldn’t fall on one or two actors to carry the whole production, which seemed like too much pressure at their age.

Still, there was quite a bit of resistance from the residents. How the heck would it ever work? A fantastical moonlit forest in a sterile nursing home environment with fairies and sprites leaping around all played by 80-year-olds, and 80-year-olds playing young lovers. How in the world would that work, they wondered. (Jilann and I wondered too!)

At one point in the discussion, a long time pro from film, tv, and theater, who was by far the most experienced actor in the room, spoke up and added, “We have no sets, no costumes, no lights or tech crew. How would we ever do this? And to do it half-ass-ugh, no thanks.” This was met by a prolonged and sinking silence, and it felt like the entire idea of the production was going down right before us. I could sense many of the seniors in the room thinking, “Well if she doesn’t want to do it, then how could we ever go on without her…”

At one point in the discussion, a long time pro from film, tv, and theater, who was by far the most experienced actor in the room, spoke up and added, “We have no sets, no costumes, no lights or tech crew. How would we ever do this? And to do it half-ass-ugh, no thanks.” This was met by a prolonged and sinking silence, and it felt like the entire idea of the production was going down right before us. I could sense many of the seniors in the room thinking, “Well if she doesn’t want to do it, then how could we ever go on without her…”

Then another resident broke the quiet and said, “We don’t need a set, we have the outside. Just stand beneath a tree, in a field, and we have spaces indoors in which to work.”

To this, another added, “Yes, all the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.”

A tangible, visible energy moved through the room, a collected sigh of relief that the group could go on, and that this opportunity ‘to get it all back’ might still happen.

And it did.

You can tune into your PBS stations starting this Saturday to watch, or you can stream the film at www.stilldreamingmovie.com.

Over the centuries it’s been common practice to spin a happy ending on Shakespeare’s tragedies. Romeo and Juliet live, King Lear and Cordelia live happily ever after.

Over the centuries it’s been common practice to spin a happy ending on Shakespeare’s tragedies. Romeo and Juliet live, King Lear and Cordelia live happily ever after.

Filmed at The Lillian Booth Actors Home just outside New York City, where a group of long-retired Broadway entertainers dive into a production of Shakespeare’s

Filmed at The Lillian Booth Actors Home just outside New York City, where a group of long-retired Broadway entertainers dive into a production of Shakespeare’s  My co-director, Jilann Spitzmiller and I went in with the idea of

My co-director, Jilann Spitzmiller and I went in with the idea of  At one point in the discussion, a long time pro from film, tv, and theater, who was by far the most experienced actor in the room, spoke up and added, “We have no sets, no costumes, no lights or tech crew. How would we ever do this? And to do it half-ass-ugh, no thanks.” This was met by a prolonged and sinking silence, and it felt like the entire idea of the production was going down right before us. I could sense many of the seniors in the room thinking, “Well if she doesn’t want to do it, then how could we ever go on without her…”

At one point in the discussion, a long time pro from film, tv, and theater, who was by far the most experienced actor in the room, spoke up and added, “We have no sets, no costumes, no lights or tech crew. How would we ever do this? And to do it half-ass-ugh, no thanks.” This was met by a prolonged and sinking silence, and it felt like the entire idea of the production was going down right before us. I could sense many of the seniors in the room thinking, “Well if she doesn’t want to do it, then how could we ever go on without her…”

A coworker challenged me to participate in NaNoWriMo, the National Novel Writer’s Month. If you’re not familiar, this contest challenges writers to create a complete fifty thousand word novel in just thirty days. Technically November is past, but there’s no reason why you can’t attempt the challenge any month you like.

A coworker challenged me to participate in NaNoWriMo, the National Novel Writer’s Month. If you’re not familiar, this contest challenges writers to create a complete fifty thousand word novel in just thirty days. Technically November is past, but there’s no reason why you can’t attempt the challenge any month you like.