Ok I’m totally blowing some family surprises here but I’m pretty sure my son doesn’t read my blog.

Recently my son, who is only 9, participated in the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust’s “Shakescraft” competition where participants were asked to build a presentation of New Place in the videogame Minecraft. Well on any given day I can’t pry my son off of Minecraft, so this seemed like a no brainer. A contest? With educational content? That happens to be Shakespeare? Deal.

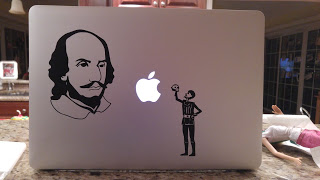

So he submits his entry, and we wait. The prize, by the way, is an iPad Air along with some Shakespeare merchandise from the store like a Shakespeare teddy bear. Of course, he spends the month hoping he’s going to win an iPad Air and trying to decide what he’ll do with it since he already has an iPad.

Meanwhile, being a dad I’m working the backup plan. I contact the gift shop at the SBT and see that I can order one of the bears directly. Hey, if he wins, great, but if he does not, I’ll ship him a bear and let him think that he at least got a participation prize.

We have to wait forever for the results, but right around Thanksgiving we find out that no, he did not win, so I put my plan into action and order a teddy bear to be sent directly to him. As Christmas approaches and packages start showing up every day I tell my wife, “Be on the lookout for one addressed to the boy from England.” I explain the story, about how she has to be the one to find it because if I tell him he got something from England he’s going to see right through the story. Also, when he finally opens it she should make sure to grab any sort of receipt in the box that would indicate that his dad paid for it.

Meanwhile, and I did not plan this timing, Christmas shopping season has begun. We encourage our kids to pick out gifts of their own for their siblings, grandparents, and yes mom and dad as well. Traditionally this has been just going down to the local $5 store since they’d insist on spending their own money, but this year as they’ve gotten older we let them exercise more variety in where they got the gifts. That also made it chaos, because instead of one big shopping run where everybody gets something (albeit something junky :)), this year was multiple trips and multiple times asking, “Ok, now, does everybody have a present for everybody?”

Going into this week, my son informs me that he does not have presents for his grandparents, or me. Well, the grandparents are easy, because every year we make mugs and mouse pads with the kids’ pictures on them. But me?

You see where this is going, right? I wasn’t sure of what was about to happen, but I had a pretty good idea.

I’m driving home from work yesterday, and we’d planned to take the kids out for a final run to the mall for last minute shopping. I call my wife to update her on when I’ll be home, and she is in the car with the kids on speakerphone. “Daddy I got you a present!” my son calls out.

Yup. It makes sense, really, because he was never about “I hope I win *something*”, he was only about the iPad. A random Shakespeare bear wasn’t going to put him over the moon. I don’t care, I’m his dad, if there was any chance at all that seeing a “consolation” prize was going to make him feel a little bit better for having made the effort, I was going to take it. But combining that with him being in the “I don’t know what to get Daddy for Christmas” situation, the results were a foregone conclusion.

So now I have to play dumb. “Huh?” I ask, pretending not to hear him on the speakerphone.

“I GOT YOUR PRESENT,” he yells again.

“How can you have gotten me a present we didn’t go shopping yet?” I play along.

You know that thing kids do when they have a long story to tell, so they pause every few words and make it a question like they’re constantly checking to see if you’re still with them? He tells me, “This package came? From England? And it said for participation? But I didn’t want it, so I’m giving it to you for Christmas!”

Well that’s just adorable, but my wife and I are both driving cars so I tell him I don’t understand what he’s saying and can it wait until we get home. I like that my wife came through on the “Oh this must be a participation prize” thing, since clearly it did not say participation anywhere on it. I notice at one point in the conversation he said something about feeling guilty, and I’m honestly not sure whether he means feeling guilty that he does not want to prize, or that he would feel guilty keeping a Shakespeare bear for himself. I think it’s probably the latter.

I get home, walk through the door where the kids are having dinner, and he explains again, “Ok, Daddy, listen. This package came today, from England, and it was for participation. It had a big PARTICIPATION sign with it.” The embellishment is amusing, because of course it didn’t say that.

“Wait wait wait,” I said, “Participation for what? What are we talking about? Oh wait is this from the Shakespeare Minecraft people? That’s cool that you got something, though, isn’t it? You don’t want to keep it for yourself?”

“I like that I got something, but you like Shakespeare more than me,” he says.

To which he oldest sister pipes up, “Ya think?”

And my middle darling offers, “Daddy *loves* Shakespeare.”

So I know what I’m getting for Christmas 🙂