So, what to do? An expectation has been set – by me, by my daughter, by her friends – that since she’s grown up with this stuff, she will walk through Romeo and Juliet. Then she opens the text and is lost just like everybody else.

I knew what I had to do. I fired up the home video server and went to the 1968 Zeffirelli movie, which I’m pretty sure they’re going to watch in class (some classes have already sent around a permission slip because of the infamous nude scene).

I quickly realize this isn’t going to work, because they’re not on the text. My daughter’s got the text in her lap and fully plans to use the video as a supplement to the source material, and right from the start, this movie is writing its own text.

Well that’s not going to work. Hello again, Mr. DiCaprio. I don’t think I ever would have imagined using Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 Romeo+Juliet to help my daughter with her homework, but here we are. Say what you want about the acting and the directing, but the thing is they actually are using the text. And I think that’s important. Right within the first few minutes, during the showdown at the gas station, the whole “bite your thumb at us” scene really gets the point across. There’s real tension there, like it could all explode at any moment. Which it does, by the way, as if this was a Michael Bay film.

Picture it. I’m there manning the remote control, pausing and declaring, “Shh! This is the best part!” every other scene. I realize I sound like my son when we tell him to turn off the YouTube video he’s watching for the twentieth time, but I don’t care. To me they are all the “best” parts because what I really mean is, “This is something you should not miss.”

This is how the afternoon went. My daughter’s got the text in her lap, and periodically looks up at the screen, then flips a page to catch up to where they have skipped. She’s clearly not doing that thing teachers fear where the students say “Forget this, why read it if I can watch the movie?” We’re doing this voluntarily before the assignment has even begun specifically so that she can deep read the text later.

While the movie is going on, we get to what’s always been my big point. Friar Laurence comes on scene, and I pause. “Something to consider,” I tell her, “Is whether you think Friar Laurence is a good guy or a bad guy.” Or why some people chose to interpret Mercutio as gay. Or whether Lord Capulet is a good father who has a bad moment later in the play, or if he never really meant everything he said to Paris in the early scenes. “This particular movie,” I tell her, “will make choices for all of those questions. A different production would make different choices. When you read the text, you get to decide for yourself which interpretations you think are correct, for your vision of the play.”

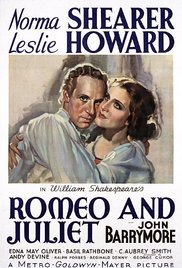

I just realized, writing this, that I also have the Norma Shearer / John Barrymore 1936 Romeo and Juliet. May have to fire that up and see how it handles the text, for comparison! Can’t have her seeing just the one version and using that as her baseline for future interpretation.

We’re on school vacation so it’s still a few days before they actually start studying the text for real. I have no idea if the teacher is going to do what they did to me thirty years ago, working through it a line at a time and not letting any word go unanalyzed. “What do you think he means by carry coals?” “Who cares?” Maybe teaching methods have gotten a little more … flexible, since my time? I have no idea. Whatever it ends up being, all I know is that I’ll be right there with all the tools at my disposal to make sure she’s got everything she needs.