For No Shave November I immediately went into the text and searched for beard references to talk about. There’s a good one in the Seven Ages of Man speech in As You Like It:

And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth.

Something I never really thought about … what’s a pard?

Just about everybody says, “Oh, that means leopard.” Which I’d accept, except for the fact that, well, a pard is actually a thing. Sure, it’s really just the mythical parent creature of a leopard (which is supposed to be the offspring of a lion and a pard – get it? leo+pard?). But I still found it interesting that everybody was glossing over something potentially so obvious.

The Wikipedia page linked above cites the Aberdeen Bestiary, which dates back to the 12th century.

Here’s where the journey gets interesting. Remember in the first Harry Potter book, where the kids hear the name Nicolas Flamel, and Hermione realizes that she saw a reference to him in a book in the restricted section?

I remember my first visit to the Folger Library, where I was introduced to a book called “The Historie of Foure-Footed Beastes“. So naturally I thought, “Is pard in that book? I must find out!” (Unlike in the Hogwarts restricted section, the librarian actually encouraged my perusal of this particular book. But I would never have thought at the time to look for a pard.)

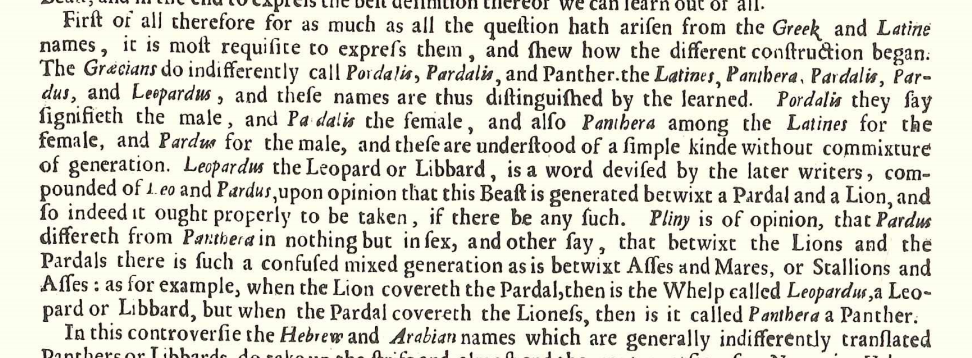

I love that I have resources now. It didn’t take long for our own resident wizard Bardfilm to produce the relevant pages:

“Leopardus the Leopard or Libbard, is a word devised by the later writes, compounded of Leo and Pardus, upon opinion that this Beast is generated betwixt a Pardal and Lion, and differs from Panthera in nothing but sex, and other say, that betwixt the Lions and the Pardals there is such a confused mixed generation as is betwixt Asses and Mares, or Stallions and Asses : as for example, when the Lion covereth the Paral, then is the Whelp called Leopardus, a Leopard or Libbard, but when the Parda covereth the Lioness, then it is called Panthera a Panther.”

What this does not tell us, at least as far as I’ve been able to read, is what kind of creature a pard or “pardal” was in the first place!

I haven’t given up the quest quite yet. I’ll let you know if there are any new discoveries!

This month’s posts are sponsored by No Shave November. To help raise cancer prevention awareness, and some money along the way, all proceeds from this month’s advertising, merchandise and book sales are being donated. If you’d like to support the site by supporting the cause, please consider visiting my personal fundraising page linked above, where you can make a direct donation.

It’s both a bit more simple and complicated, in short: of the cats greater than the wild cats of Scotland, the classic authors knew of the lion, the panther (modern meaning Panthera pardus), the tiger, the cheetah and the lynx. There are good reasons (probably related words in Indo-Iranian and the like) to assume that the original pard was just your “leopard”, with the relatively easily tamed but notoriously hard to breed cheetah was the original supposed hybrid “leopard” (still a “Jagdleopard” in German and “jachtluipaard” in Dutch), which would probably have been the meaning of pardal too, if and when it was used to indicate another species than the pard, rather than being used as a sex indication, like lioness or tigress.

With cheetah and panther both being spotted cats, and the lynx being that too,, confusion between cats became a thing, so it is hard to guess whether the leopard, pard or pardel talked about is a panther, cheetah, lynx, an amalgam of those formed by confusion or even something else, like an actual lion x pather hybrid, or an early report of one of the at-the-time-still-undiscovered cats.

This was going on for centuries before the 12th century, so the same words found in different languages, classes, ages and lands could mean things like panther, cheetah, lynx, sometimes restricted to a specific species or sex, and even indicate a mere domestic tomcat. So the confusion kept growing, and the bestiary is just trying to make sense from, if not conflicting, still confusing texts about actual animals we still can see in our zoos. No need for any mythological or fantasy creatures, the pard refers to a fully natural, be it perhaps slightly misunderstood cat, but which cat?

The word used by the Bard

did once indicate leopard,

but, so verily wonder we

it did, but did also he?

Strongest is the roaring panther

prey hider in tree and cave in stone,

but, unknown to Diever’s enchanter

in speed the other pard runs all alone.

Full but short of hair a chin,

both have, and the tomcat too,

too short for grabbing for a win,

as killers for living will do.

The really best bearded pard,

no doubt the lynx would be,

that election hardly hard,

such whiskers clear to see…

But what did Avon’s Bard really know,

how was that soldier’s chin to be seen?

Unshaven but short trimmed to go

or looking like Logan the Wolverine?