I’m going to say something up front because I had it said to me (well, I read it), and it helped me enjoy the movie “Sing Sing“. This is a true prison story. But there are no riots, no escapes, no makeshift shivs sticking anybody in the back. It’s not that kind of story. That’s not a spoiler, that’s permission to breathe, relax, and appreciate what’s really going on in the movie. You don’t have to watch in fear that something bad is going to happen.

I admit that I dismissed Sing Sing at first as just another take on “Shakespeare Behind Bars,” which I first saw twenty years ago. That was a mistake, I’m happy to say.

Sing Sing is the best movie I’ve seen in a long time. Too often I’ll watch a movie in that half-listening, “put it on in the background” way that we sometimes do when we treat an item like a todo-list box to be checked instead of an experience to be savored. Not this time. I was hooked in the first minutes. I put down the computer and sat on the edge of my couch cushions straight through to the end.

This movie tells the story of Sing Sing prison’s Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program. It focuses on the story of John “Divine G” Whitfield, a playwright himself and original member of the group, played brilliantly by Colman Domingo. We also learn that he’s incarcerated for a crime he didn’t commit, and on a continuing quest to prove his innocence.

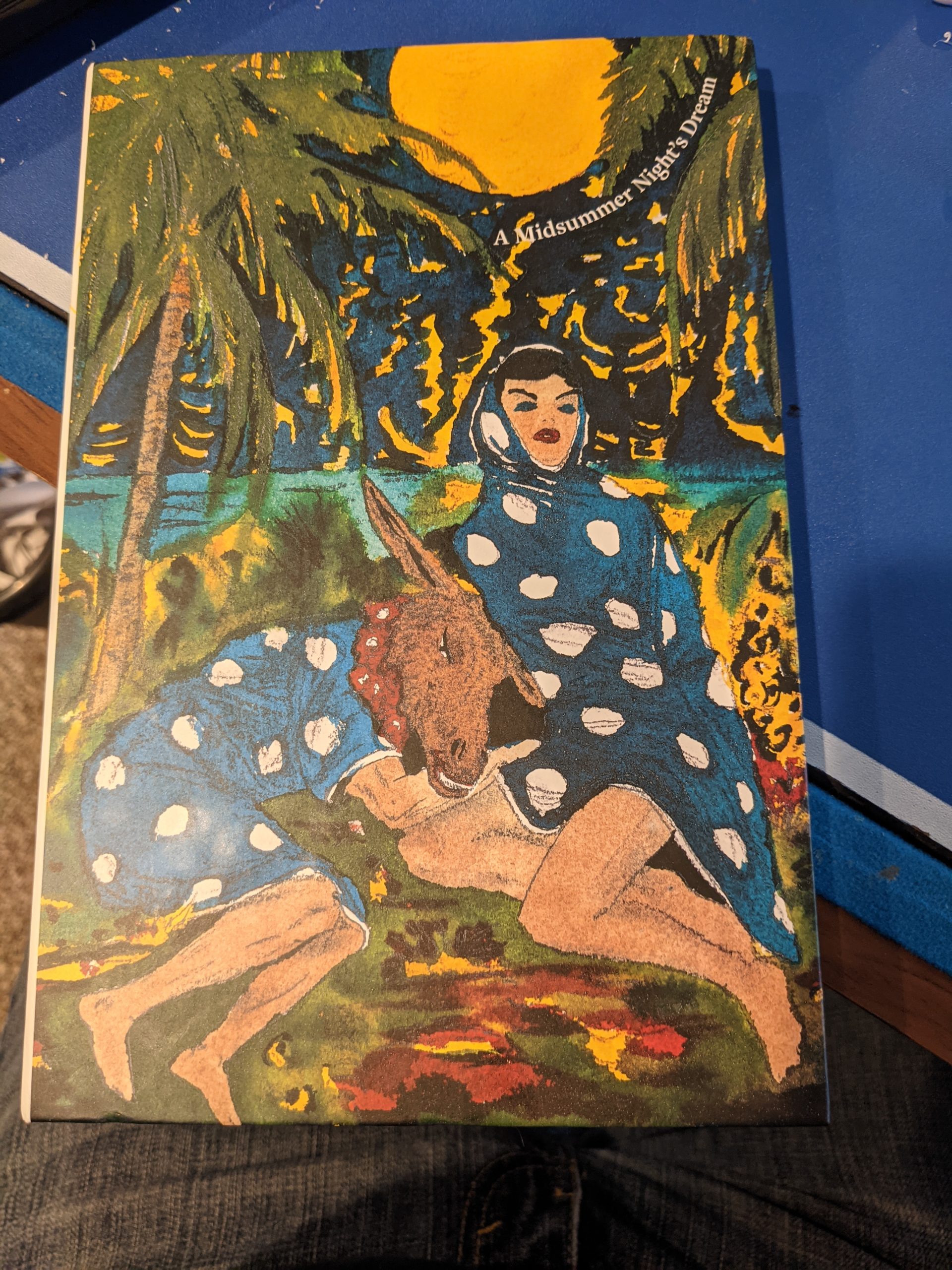

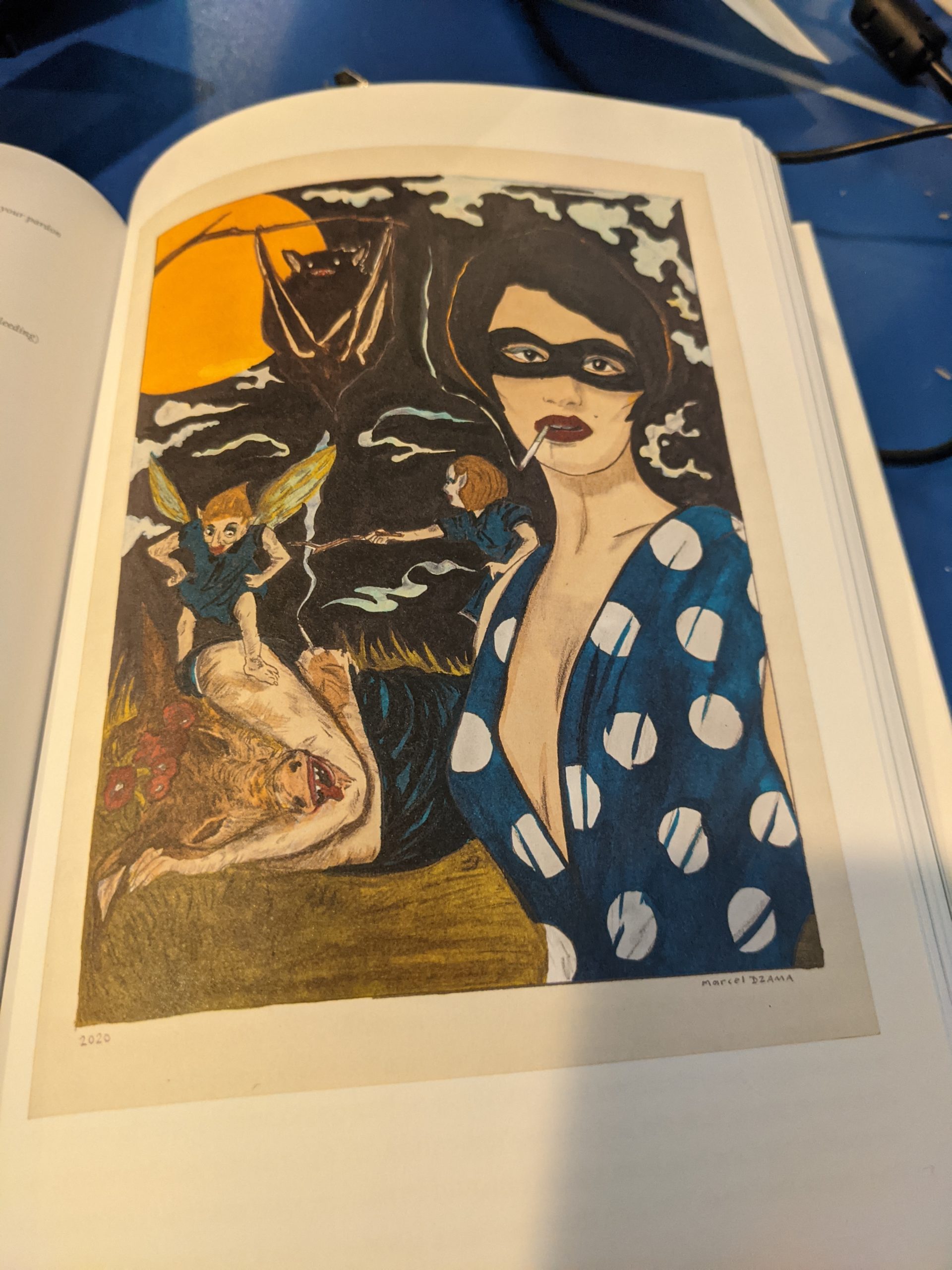

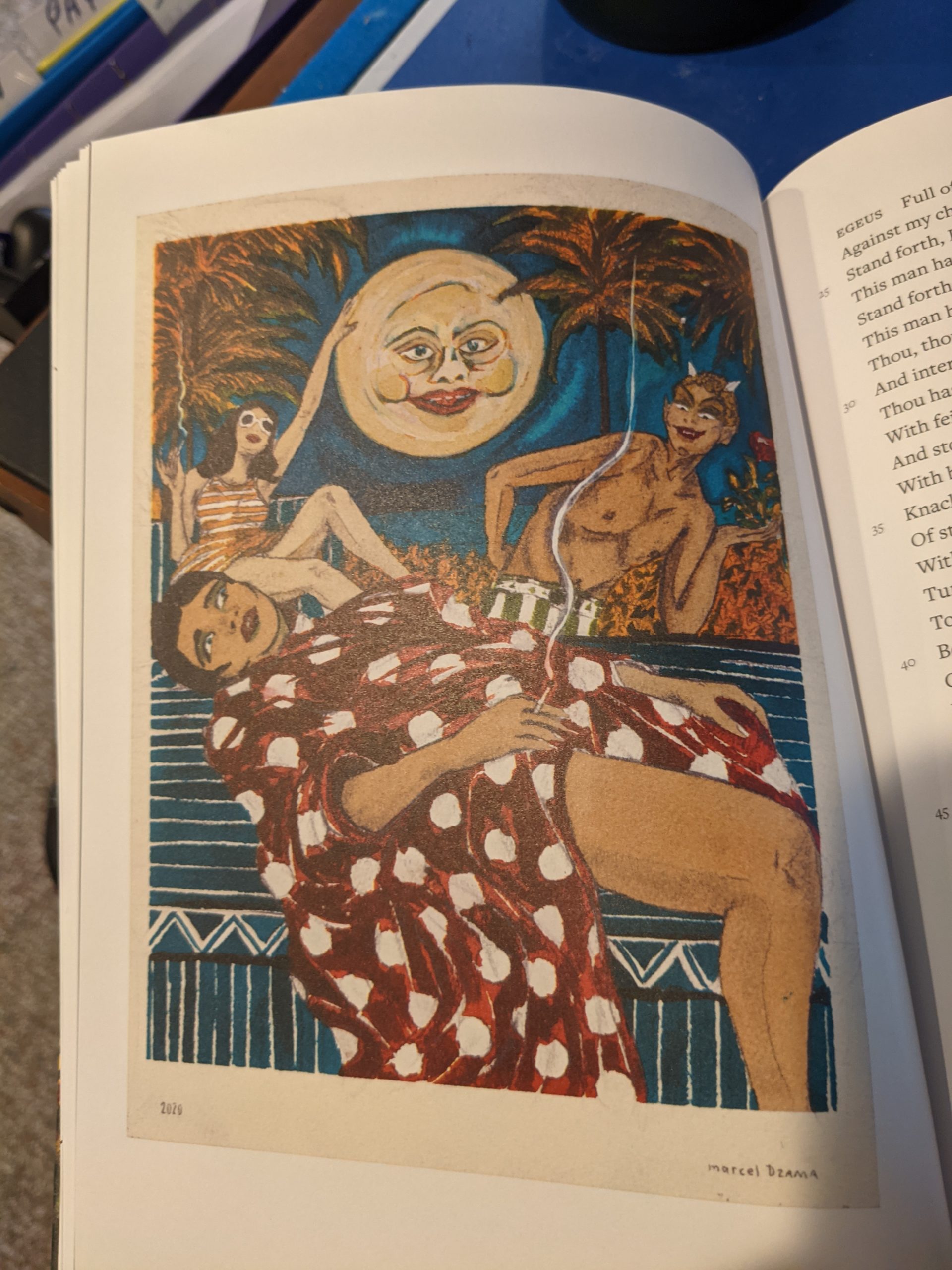

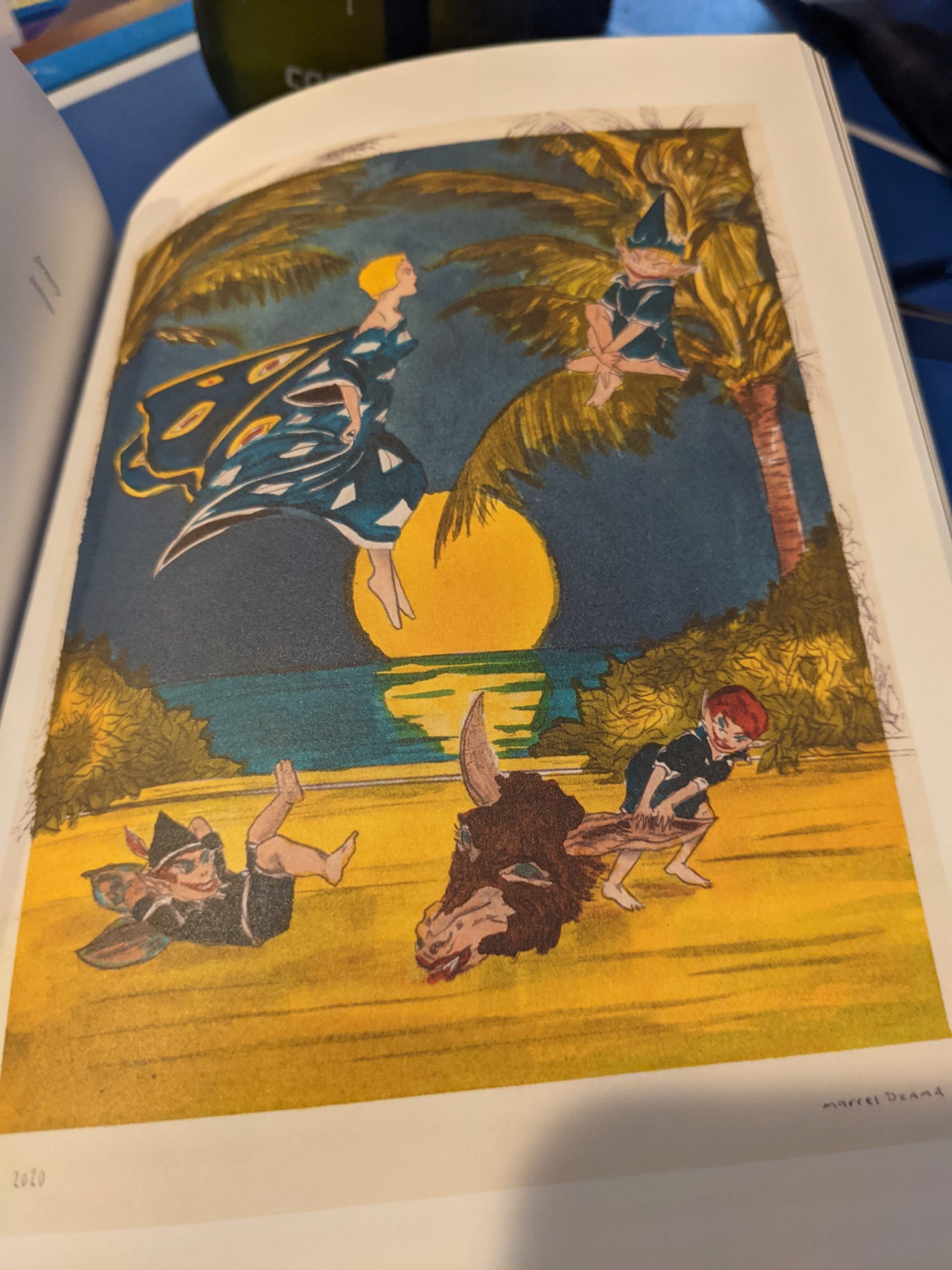

We open with the close of the group’s most recent performance, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and the addition of new members to the group. Here we meet Clarence “Divine Eye” Maclin, playing himself. One of the fascinating aspects of this movie is that it’s based on a true story and played by many of the actual original players. If, like me, you’re wondering how the two main characters ended up as “divine” something? Well, that’s not the writing, that’s the reality. Those were their names.

Despite Divine G’s insistence that Divine Eye be admitted to the group, there’s some immediate animosity at Eye’s strong new personality. G is thrilled when the other members of the group suggest they perform one of G’s original plays next, only for Eye to sway the group that a comedy is the way to go. But then they both audition for the only dramatic role in the script (an original, created by the group’s director).

This sets up the first of many confrontations between the two. G loves the program and knows what it’s done for the other inmates. Eye comes from a world where if someone so much as walks too close behind you, your life might be in danger. The evolving relationship between the two is the our major story arc.

What About The Shakespeare?

This is a Shakespeare blog, so let’s talk about Shakespeare. This isn’t a Shakespeare movie. They don’t perform Hamlet in the big final act. But somehow, that makes it an even better depiction of why Shakespeare is universal.

We find out that Eye became interested in theatre after stumbling across King Lear as one of the few books accessible to him. Unprompted, he quotes, “When we are born, we cry that we are come To this great stage of fools” with no fanfare, no “Look at me I’m quoting Shakespeare,” no flourish or fanfare. His interpretation actually made me laugh, saying that “whoever wrote this, man, had to did a bid before.” The idea that Shakespeare can just pop into your life, at any time and place, and you don’t even know what it is, but it still resonates, no matter who you are? Come on now. What have we been trying to say all these years?

There is more Shakespeare than that, not to worry. Despite the play being an original time travel comedy featuring time travel, pirates, and zombies, it also features Hamlet. (If that makes you think of Hamlet 2, you’re not alone.) Eye, of course, is playing the role – which affords G the opportunity to direct him. The actual director of the group is not an inmate, so while he can speak to the theatre, he can’t speak to the experience. That’s where G shines. He helps Eye break through from “I walked on stage and said the lines” to “I am the character.” It’s really quite a thing of beauty to behold.

I’ve often said that a key to understanding Shakespeare is realizing that, underneath the words, “there are people in there.” Well, that’s true here, too. These are prisoners, but they are people. There are multiple scenes where they talk about their children, their lives outside the prison, and how they got there. There’s a scene where they all meditate on their “happy place” and talk about it, and an inmate realizes that his happy place is right there, right now. He is happy where he’s found his people.

I could keep on like this, describing the scenes I loved, but I’ll tell the whole movie. There is a story that we want to see resolved. Eye, knowing he’s innocent, struggles to get out – no matter how much value he’s found in the RTA program. G, who slowly but thankfully becomes part of the RTA program, can’t imagine any world other than the one he’s made for himself. Both these characters are changed individuals by the movie’s end credits.

One more scene, and then I’ll wrap up. During an early confrontation, Eye is still throwing around N-words like they’re part of the normal prison vocabulary. “We don’t say that here,” G tells him. “We say beloved.”

I get it, I think, at least as much as a white person can. Both, in their way, are expressions of a bond that exists, a way of saying, “We are the same, we come from the same world, there are things that we share that not everyone shares.” But they can achieve the same purpose and still be completely different ways of doing it.

And at first, you think, “Yeah, sure.” This is the guy still packing a knife in his waistband, ready to cut one of his fellow actors just because the blocking called for him to get a little too close. But you know what’s going to happen, And when it does, it’s … just so natural. The director doesn’t call your attention to it with over-the-top background music. There’s no meaningful pause for the audience to have their “Ohhhhhh, ok!” moment.

That’s why I love this movie. You don’t spend the whole time thinking, “Somebody created this story, somebody wrote a script, somebody directed it and told the actors what to do and where the camera should look.” This isn’t just a real story, many of the original actors perform the story including Divine Eye. If you love something about it, love it more because it really happened. It’s not someone’s wishful thinking. Score one for Shakespeare.